Lessons learned photographing Iceland

My wife and I traveled to Iceland in June. As with any vacation, the excitement ramped up as our departure neared. What caught me by surprise, however, was the buildup in pressure (no geothermal pun intendend) to “get it right.”

What was “it,” and why did I need to get it right? The answers were “the pictures” and “because of all the once-in-a-lifetime wonders that cannot be found within driving distance from home.”

Like any other self-respecting person who considers themselves creative but does not get paid to take photographs, I already knew that I was a “halfway decent amateur photographer.” I had an autofocus DSLR camera (that was used, at most, once a year), I always followed the Rule of Thirds, looked down my nose at Instagram filters, and never locked my knees. (That’s because a photojournalist and former co-worker at WQAD told me that. Once. In passing.)

Clearly, I knew my stuff. …Right?

(“It’s not Wingardium Barthalon-AH, It’s Wingardium Bartha-LOOOOON-a!”)

In the final month preceding the trip, we were watching just about any video we could find on Iceland. I watched and re-watched one professor’s video on how to pronounce all the ð´s, þ´s, and æ´s until I sounded like the kind of guy who lived to stop a group conversation dead in its tracks to ensure that everyone’s correctly pronouncing Barcelona.

I don’t care. It’s fun to say Eyjafjallajökull.

…The point is, I also saw how unprepared I was to capture the beauty that would backdrop our trip. I set out for a book to help me out. I bought John Shaw’s Guide to Digital Nature Photography and read that 2-3 times. Once for the gear recommendations, once for the entirety of the content, and once more to double check the gear I actually needed for the trip. While I didn’t follow Shaw’s recommendations like a multiple-choice shopping list, I did feel informed enough to understand why I went a different way with certain things (not that my way was best, it felt like the best for me at the time).

All in all, this book went a long way toward giving me enough of a foundation on which I could work. At the very least, it saved me from second-guessing every single decision I made.

Here are some supplemental lessons I learned, and by “lessons,” I usually mean ´’mistakes’ or ‘misconceptions’ that tripped me up. None of them are life-changing or groundbreaking, but if even one of these manages to save you a headache, then great.

(I’ll be posting a several collections of photos from Iceland over the next couple of weeks, and I’m sure they will determine just how big a grain of salt you should take with them.)

In his book, Shaw walks the reader through most of the “basic” features and settings you’ll need to get the most out of your DSLR, including the menu settings you’ll need to adjust. He specifically mentioned updating the clock, but between practicing flipping through histograms and clipping on the rear LCD display, and getting to the right exposure compensation or shutter speed in something better than a flail or fumble, I figured I’d save the easy one for last.

And I did do that last. I did it the day after I got back from Iceland and saw that all my pictures were created 3 days, 5 hours, and 42 minutes in the future.

After spending the better part of a day trying to find the best way to “quickly” batch update all of my photos, I finally settled on Exif Date Changer, which had the right balance between price, functionality and ease of use.

NOTE: If you use it and rely on file names in any aspect of your image organization, click on the Options tab and uncheck “Rename files to.”

Seriously though, be smarter than me and really remember to update it before your trip, especially if you’re going to cross more than a couple time zones.

Even though our boys were not coming with us, I knew that as soon as I got out a tripod, I would be holding up my wife and, on occasion, her friend’s family. I bought a roughly $40 tripod with flip locks and practiced setting it up and tearing it down (15 seconds both ways, for what it’s worth). Not the most useful of life skills, but I suppose it’s nice to have it when it counts.

My wife wanted two basic things from me: A “best of group” for when we strap down our friends and family to chairs in order to force them to see the photos, and a 100-photo subset of the first group that will be saved as a collection of 3×5 prints. (I, of course, had plans of my own for the collection.)

After spending way too much time since our return on evaluating, tweaking, and organizing my photos, here are two things I wish I would have packed, luggage restrictions be damned:

A cable to run from my camera to a standard HDMI port. I took more than 980 photos. I easily had one or two hundred photos that were either just a little too blurry, over- or underexposed, or composed in a way that did not live up to what I had hoped. Some of them were easy to pick out from the display on the back of my camera, but it would have been nice to review it on our B&B’s screen.

NOTE: Since we returned from Iceland, I’ve viewed these photos on three televisions, and the images looked noticeably different in each. Just something to bear in mind.

A netbook or tablet attached to an SD card reader. It just makes it easier to rename, tag, organize, and even upload your photos if necessary.

Bluffs surrounding Geysir Hot Spring Area, Haukadalur Valley, Iceland. (Photo by Michael Gorman)

It’s easy to fall into hyperbole, so I’ll just come out with it. There were so many waterfalls big and small, so many hills and bluffs with their bases covered in Nookta lupine, so many mountaintops shrouded in low-lying clouds that by the end of the trip we started to get picky about which ones we wanted to photograph.

If that wasn’t enough, nearly our entire trip was spent within two degrees latitude of the Arctic Circle a little over a week before the summer solstice. This allowed us to go to dinner at 5 p.m. and still do the Geysir and Gullfoss parts of the Golden Circle by 9 p.m., drive down the backroad to our friend’s cabin afterwards, the whole time spent in a beautiful, elongated sunset.

I can’t speak for anyone else, but it certainly felt like there were not only a lot of opportunities, but also the flexibility to take advantage of them. Even I couldn’t overthink some of these situations–and I’m the kind of guy that brings spreadsheets to an art-fight (see below).

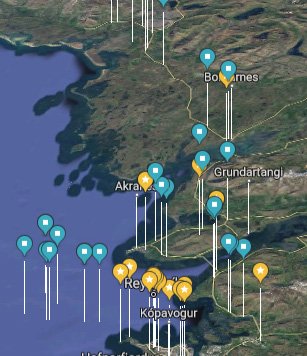

I added some pins after the trip to help with updating the GPS location in the photos.

Knowing I wasn’t going to really process any photos until after we returned home, I needed a quick way to keep track of the various places we stopped to help jog my memory.

We didn’t get the local sim card, but I did download offline maps of the whole island, and whenever I wanted to note a location, I saved it in Google Maps.

It worked well enough. The only issue remaining was the awkward GPS format Adobe Bridge required. instead of either being straight decimal or degrees/minutes/seconds, it needed to be typed in as DD,MM.SSSS(N or W), and it threw up an error message if you fat-fingered any of the entry and try to tab or click away from it.

Luckily(?), I find that spreadsheets can be just as handy in everyday life as duct tape. I created a sheet with a column for minutes, seconds, and degrees, and it converts the minutes and seconds into that awkward MM.SSSS format.

=A2 + ((((B2 - MOD(B2, 6))/6) * 0.1) + ((MOD(B2, 6)/6)) * 0.1)

In this case, A2 is the “minutes” cell and B2 is the “seconds” cell. A latitude with 16 minutes, and 5.7 seconds becomes 16.0950. With a little bit of extra work, I could (and probably should) have just finished the job and combined the degrees, comma, and direction into one string output, as I already figured out the hard part of the formula.